|

| September 15, 2015 | Volume 11 Issue 35 |

Designfax weekly eMagazine

Archives

Partners

Manufacturing Center

Product Spotlight

Modern Applications News

Metalworking Ideas For

Today's Job Shops

Tooling and Production

Strategies for large

metalworking plants

Wings:

NASA tests 3D-printed rocket fuel pump and paves way for 3D-printed demonstrator engine

By Tracy McMahan, NASA Marshall Space Flight Center

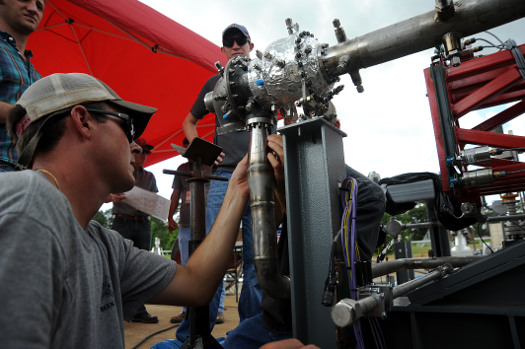

Engineers prepare a 3D-printed turbopump for a test at NASA's Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, AL. [Credits: NASA/MSFC/David Olive]

One of the most complex, 3D-printed rocket engine parts ever made, a turbopump, got its "heartbeat" racing at more than 90,000 revolutions per minute (rpm) during a successful series of tests with liquid hydrogen propellant at NASA's Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, AL. These tests along with manufacturing and testing of injectors and other rocket engine parts are paving the way for advancements in 3D printing of complex rocket engines and more efficient production of future spacecraft.

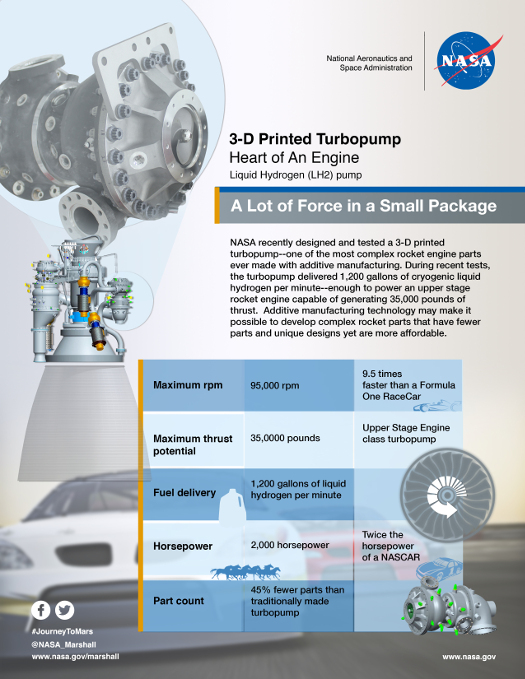

This rocket engine fuel pump has hundreds of parts, including a turbine that spins at over 90,000 rpm. The turbopump was made with additive manufacturing and had 45 percent fewer parts than pumps made with traditional manufacturing. It completed testing under flight-like conditions at NASA's Marshall Space Flight Center. [Credits: NASA/MSFC]

Additive manufacturing, or 3D printing, is a key technology for enhancing space vehicle designs and enabling affordable missions to Mars. The turbopump is a critical rocket engine component with a turbine that spins and generates more than 2,000 hp -- twice the horsepower of a NASCAR engine. Over the course of 15 tests, the turbopump reached full power, delivering 1,200 gal of cryogenic liquid hydrogen per minute -- enough to power an upper-stage rocket engine capable of generating 35,000 lb of thrust.

"Designing, building, and testing a 3D-printed rocket part as complex as the fuel pump was crucial to Marshall's upcoming tests of an additively manufactured demonstrator engine made almost entirely with 3D-printed parts," said Mary Beth Koelbl, deputy manager of Marshall's Propulsion Systems Department. "By testing this fuel pump and other rocket parts made with additive manufacturing, NASA aims to drive down the risks and costs associated with using an entirely new process to build rocket engines."

The 3D-printed turbopump has 45 percent fewer parts than similar pumps made with traditional welding and assembly techniques. Marshall engineers designed the fuel pump and its components and leveraged the expertise of four suppliers to build the parts using 3D-printing processes. To make each part, a design is entered into a 3D-printer's computer. The printer then builds each part by layering metal powder and fusing it together with a laser -- a process known as selective laser melting.

"NASA is making big advances in the additive manufacturing arena with this work," said Marty Calvert, Marshall's design lead for the turbopump. "Several companies have indicated that the parts for this fuel pump were the most complex they have ever made with 3D printing."

During the tests, the 3D-printed turbopump was exposed to extreme environments experienced inside a rocket engine where fuel is burned at greater than 6,000 deg F (3,315 deg C) to produce thrust. The turbopump delivers the fuel in the form of liquid hydrogen cooled below 400 deg F (-240 deg C). Testing helps ensure 3D-printed parts operate successfully under these harsh conditions. Test data are available to American companies working to drive down the cost of using this new manufacturing process to build parts that meet aerospace standards. All data on materials characterization and performance are compiled in NASA's Materials and Processes Technical Information System, called MAPTIS, which is available to approved users.

Video: This video shows a test of the 3D-printed turbopump made with 45 percent fewer parts than traditionally manufactured rocket fuel pumps. During the test, the pump's turbine spins at more than 90,000 rpm -- 9.5 times faster than a Formula One Racecar. The fast-spinning turbopump causes the vibrations in this video. The turbopump moves 1,200 gal of liquid hydrogen per minute. The hydrogen is at cryogenic temperatures below -400 deg F, and operation at these extremely low temperatures is what causes the frost to build up and flake off during the test. [Credits: NASA/MSFC]

"Our team designed and tested the fuel pump and other parts, such as injectors and valves, for the additive-manufactured demonstrator engine in just two years," said Nick Case, a propulsion engineer and systems lead for the turbopump work. "If we used traditional manufacturing processes, it would have taken us double that time. Using a completely new manufacturing technique allowed NASA to design components for an additively manufactured demonstration engine in a whole new way."

In addition to sharing test data with industry, the innovative engine designs can be provided to American companies developing future spaceflight engines. The engine thrust class and propellants were designed within the performance parameters applicable to an advanced configuration of NASA's Space Launch System (click for PDF backgrounder), referred to as Block II. It will be the most powerful launch vehicle ever built and provide an unprecedented lift capability of 130 metric tons (143 tons) to enable missions even farther into our solar system to places like Mars.

Published September 2015

Rate this article

View our terms of use and privacy policy